For over half a century, Mary Corse—an American artist, primarily working through the medium of painting—has confronted the aura and specificity of materials, experimenting with their capacity to respond to the surrounding environment. From her iconic use of prismatic, glass microspheres, to her ongoing explorations of organic materials, Corse roots her practice in the belief that the essence of painting is not specific to paint itself.

Corse emerged in the 1960s alongside the West coast, minimalist aesthetic known as Light and Sound. While she resists singular classification within this movement, she clearly relishes in the conceptual space its minimalism affords. Through a bold erasure of excess, Corse draws attention to both the psychology and corporeality of perception. It is her keen attention to the minutiae—right down to her use of beveled canvases that minimize her work’s protrusion from the wall—that makes the dimensionality of her paintings even more robust.

I was fortunate to catch up with Corse to discuss the role of the artist within the secular world, and consider three questions essential to her practice: What is seen? What is unseen? and What is real?

NICO: There is a bodily aspect to your work that seems to reward—maybe even necessitate—an active viewer. Light refracts, hues emerge and patinas shift as one moves across the surface of your paintings. I know you have described perception as the true art form at play in your work, so how much is your role as an artist tied to intuiting certain spatial relations to your work?

MARY: Oh sure, I think about the architecture, the proportions of the space, and the relation of the paintings to each other, knowing that the viewer will ultimately come in and be involved. But it is not a controlled situation that I envision in exactly one way; instead, it encompasses whatever happens in that moment. I get more concerned about the dialogue between the works, which is a conversation that of course the viewer becomes a part of. They walk around the painting or they don’t, that’s their choice. But my hope is that they can become part of the painting.

N: Can you explain how the materials themselves invite viewers to become part of the work?

M: People often think my paintings are made from microbeads that reflect light in a 1-2 relationship, but that’s a misconception. I actually use glass microspheres, or prisms that forge a triangular relationship between the painting’s surface, the light and the viewer. And at the middle of this is the viewer’s perception, which animates the work as they move and shift; so in that way, the art is really not on the wall at all, it’s in their perception.

N: Working with reflective and refractive materials, are you able to you see yourself in your work as you create it? How does the process of making the work differ from that of viewing it on the wall?

M: Before I even start the painting, I see it as a vision. I see it in my mind, similar to how we see images in our dreams. But when I’m working on the painting, it’s a totally different experience from when I step back and see it in its entirety. It’s a different kind of connection; I can’t wait to see it, but I’m so caught up in the process that I don’t actually see it at all. And it could drive you crazy, all the layers, all the sanding, and you don’t even know what you have until dusting off the final layer. And if there is one brushstroke that I don’t like, it can ruin the whole painting. But I don’t see it in this final state until its done and I am in the same position as the viewer.

N: Have you ever had an unveiling moment where the final piece was so far from your vision for it that you were unable to work with it anymore?

M: Absolutely. When that happens, there is no working with it. Its over and there is no fixing it or going back. That’s just it, because it is all happening in the moment. The painting is on the floor, I am over it painting and pouring beads, and my assistant is pulling me back and forth on this long board with wheels, and we just keep going and going. Some people can work on a painting for years, forever, which would drive me crazy! So in a way it’s OK that it’s over when it’s over, regardless of the outcome. I either made it, or I didn’t.

N: I understand that feeling well. I think it is similar to any process where you throw yourself in completely, both physically and emotionally. There must be an end or else the process can end you. What are the physical challenges to painting intuitively, and have you ever had an idea for a work that you were unable to visualize?

M: After ten years of making white paintings in the sixties and seventies, I found myself in the mountains molding these black, earth tiles. Before that, I hadn’t made a painting smaller than eight feet. I had to design and build this kiln, in which I managed to make a four square foot tile. At the time, that was the world’s largest tile, and all the kiln builders had said it would never work. While I haven’t realized that project yet at the scale I intend to, at least I kept at it until I found the way to do it. It was a real earth slab factory I had going on out there in Topanga Canyon, right off a quiet dirt road up in the mountains.

This was in the seventies so I really had no funding; I mean, all I needed was an extra ten thousand dollars, you know, and I could have done it right then and there! Richard Bellamy was supportive to a certain extent, but those kinds of experiments cost a lot of money. I made a lot of experimental progress, but before I could get the rest of the funds together for that, I had moved on to making these black on black glitter paintings. The slabs took me in that direction. But I still plan to make that earth tile piece one day.

N: You mentioned working with an assistant at times when you are building larger armatures to support your work. But, outside of that, is your process pretty solitary?

M: Its solitary for sure, that’s the part I like. At certain stages of the painting, I need to work with others, although artists are totally sensitive to the psyche of others, and that can affect the work. But at other stages, you have to be alone, because that’s when you start having a conversation with the bigger picture, and transcend thought to enter into a different context. For me, the solitary act of painting reminds me to consider and keep track of the questions, Who am I? and Where am I? Those questions keep me going.

N: When I consider these heavy questions, and your commitment to carrying them through each step of your process, it becomes clear how deeply philosophical and metaphysical your work is. It makes me wonder if your work might not also be considered political, at least in its pursuit of truth.

M: There is no political intention in my work. My interest is in getting out of the finite, thinking, particular realm which politics is certainly imbedded in. To me, even a point in time exists within the finite world. When I’m painting, I want to have a conversation with the infinite, with the multiverse. Right now, I assume we are both in a building, and that we have roofs over our heads. But actually, what’s really touching the top of our heads is outer space. We forget that this is where we are, and I’d rather be curious about that than any particulars. The political is so small compared to Who am I? What am I? and What is happening? I want to know what’s happening on the unseen levels. When I’m painting, I can have that conversation and the paintings give me those answers. And if people like the painting, then they are getting some kind of answer too.

N: And how does context help you to answer these questions? How do you see yourself in relation to art history, contemporary practice, and what you perceive to be the future of the field?

M: There is definitely an evolution of painting, and I function within this artistic context. I was first really influenced by early, New York abstraction. At age fifteen, I was tracing works by de Kooning and Hofmann. And I think there are a few lineages: the conceptual lineage coming from Duchamp, and the painting lineage coming from Cézanne and Manet. I’m very interested in the evolution of ideas, perception and consciousness in art, as they relate to everything else. And this is where physics comes in.

N: In a past interview, you stated, “part of me thinks that physics and art are two sides of the brain, they sort of parallel one another in their discoveries.” Can you unpack this a bit more?

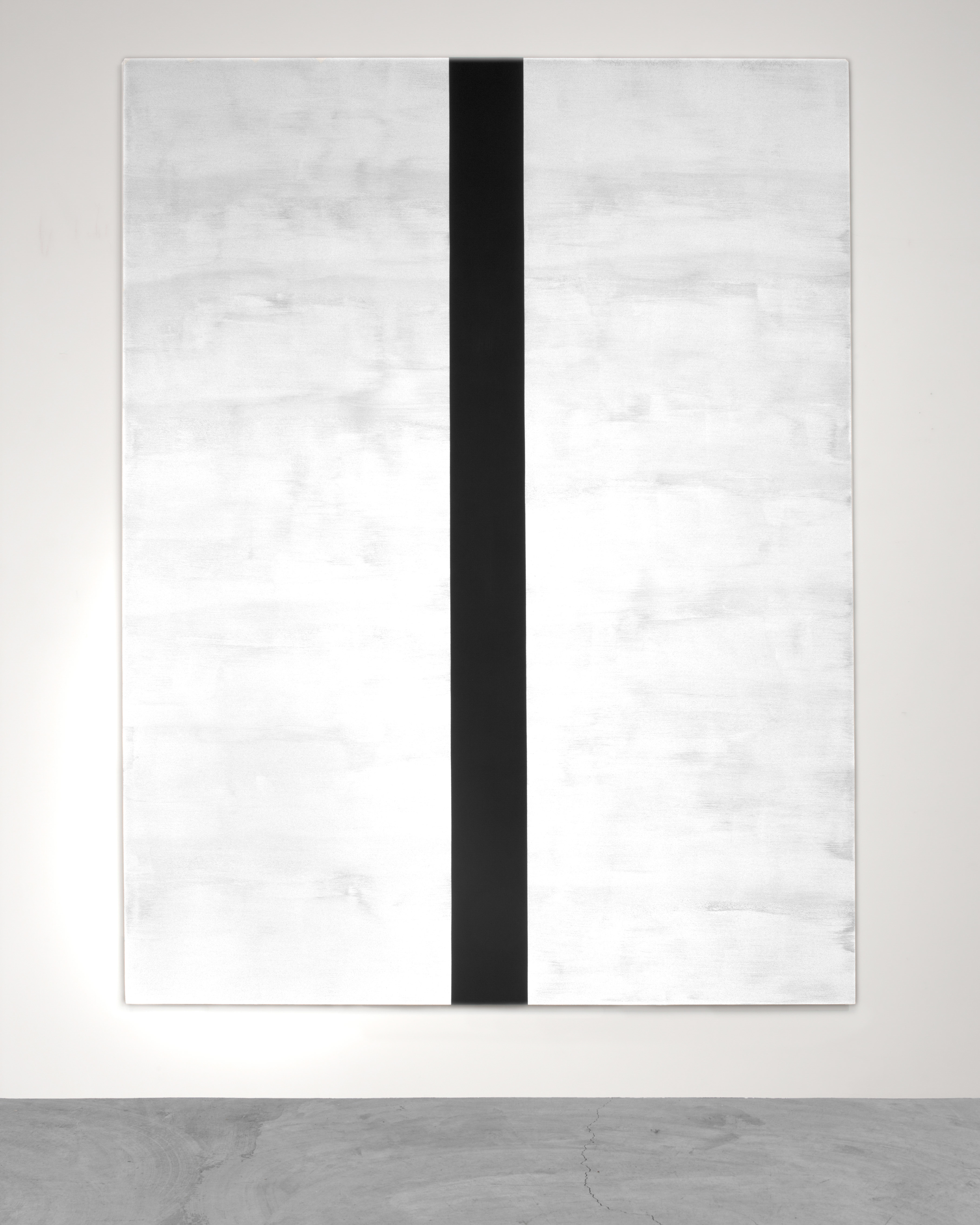

M: You know what I say? I think it’d be great if humans could use both sides of our brain, equally. Art and physics share the goal of trying to describe and make seen the unseen; physics uses a formula, and the artist uses proportion and shape. Physics, or what is now metaphysics, says that reality is perceptual. And that’s why art now has to be saying the same thing. I have really been playing with the inner band in my paintings, which is an inner dimension that appears and disappears as you move around it. I learn from each one of my paintings, and when I step back, I can see that whatever it is that the artists and the physicists are talking about is real.

N: What about synaesthesia, or the union of the senses? I’ve read that you are able to see energy in this inner band, especially between the white and black in your monochromatic works. Are there any other sensory impressions you experience or seek to insert into your work?

M: For years, the center band in my paintings was white, and then I transitioned to placing black at the center. The optical energy between the white and black is so flashy that it creates a white energy field across that black. And I realized this was the whole point, seeing the unseen. Energy is fascinating and the most elusive of all; we only see what it’s done, the direction it is going, or the trail it has left behind. But do we really see energy? The desire to understand and see energy is similar to the desire to understand and feel love.

From childhood, we are told what the limits are, what we can see, touch or hear. Imagine if we weren’t told from the time we were born what is possible and what is impossible? I am interested in the experience before the concept, before we conceptualize it. And who knows what we actually see in that moment, because we are so trained and conditioned. One of the things about painting is that it sheds this conditioning, sheds the surrounding culture, and returns you to your original being.

N: Do you think art evolves in the same ways that science does? The way I see it, science is always making visible progress, drawing attention to some previously unseen aspect of the finite pool of matter that’s existed on earth forever. But a critique I often hear of contemporary art is that there are no new ideas, and that everything has been done before. That, somehow, the pool of conceptual matter actually becomes bankrupt over time. How do you respond to that?

M: I don’t know, but I think it’s amazingly interesting! Do you know that, right now, scientists are sending photos from Pluto? I wish the whole world would catch up with the potential of human consciousness. But we are still here, on primitive planet Earth. I’m big on freedom and experiencing who you really are in the moment, and not being so created by culture that your creative self isn’t really there. To really be creative, artists have to go beyond the thinking mind. That’s not where art comes from. I question how people can live their entire lives without exploring this freedom.

I am a realist looking for something that’s true. I want to have a true moment; I don’t want to live in a fantasy about the future, or be nostalgic over the past. I want to be right here, now, where there is no time. I’m big on that, living your life in the moment. That’s why I resist technology. People aspire to be like machines, and we are getting to be more and more mechanical. I worry that someone has to keep this true art connection happening, or else we will all become a bunch of robots.

N: And what excites you now, Mary? How do you plan to keep this true art connection alive?

M: I want to continue to bring paintings outdoors. My interest in outdoor pieces is ongoing. I want to do more paintings on the sides of huge buildings, and do a freestanding piece in the desert. I’ve had these ideas for twenty years, and am happy to finally be getting around to it.

---

Mary Corse (b. 1945, Berkeley, California) received her B.F.A. from the University of California in 1963, and her M.F.A. from the Chouinard Art Institute in 1968. Corse’s work was recently exhibited in several historically significant exhibitions including Venice in Venice, a collateral exhibition curated by Nyehaus in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum at the 54th Venice Biennale (2011); Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, Germany (2011); Phenomenal: California Light and Space, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (2011). Her works are in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Fondation Beyeler, Basel; Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation Collection, Los Angeles; Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego; Orange County Museum of Art at Newport Beach; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and other institutions public and private. The artist lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

Published in NOTOFU Magazine, Summer 2016 Issue