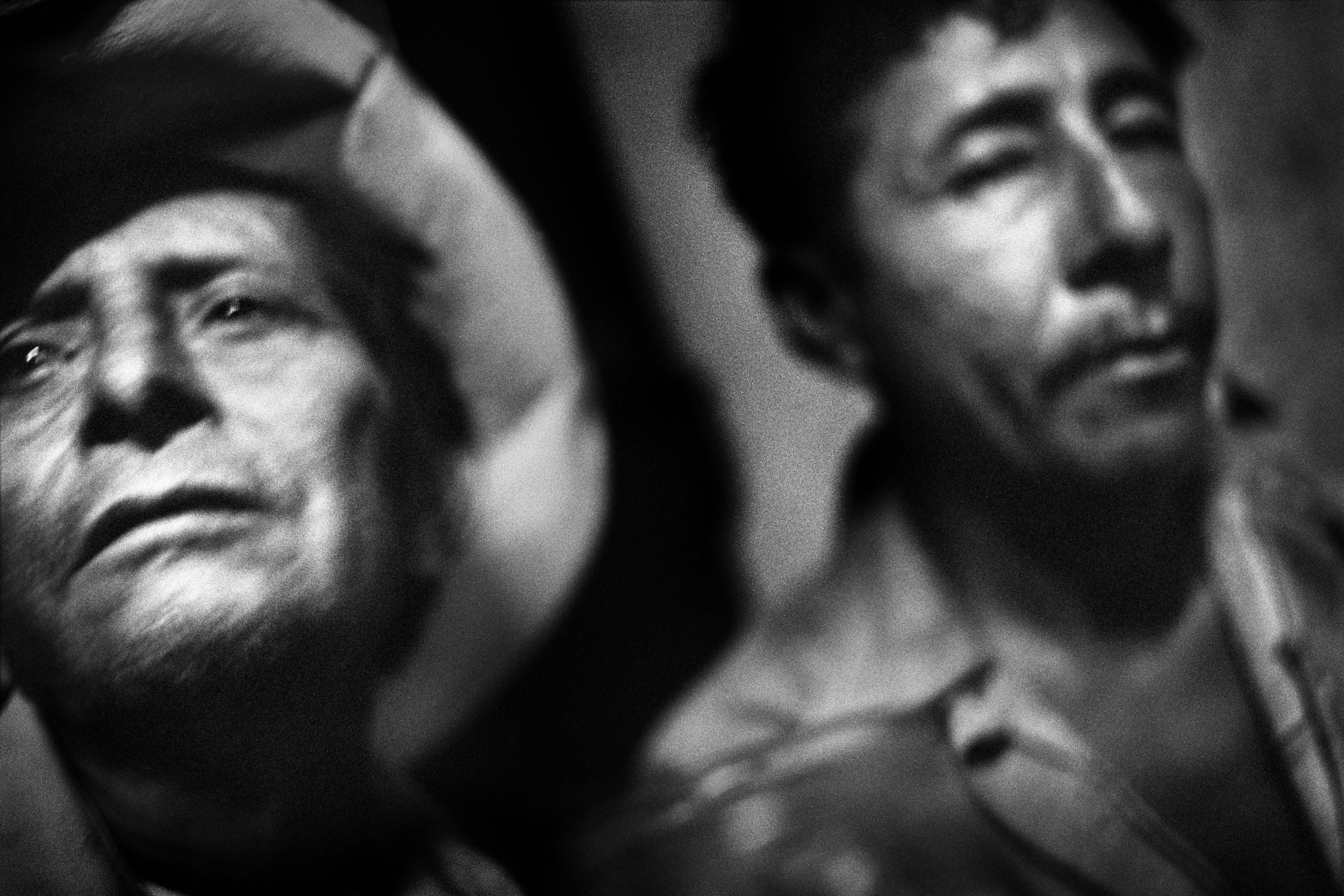

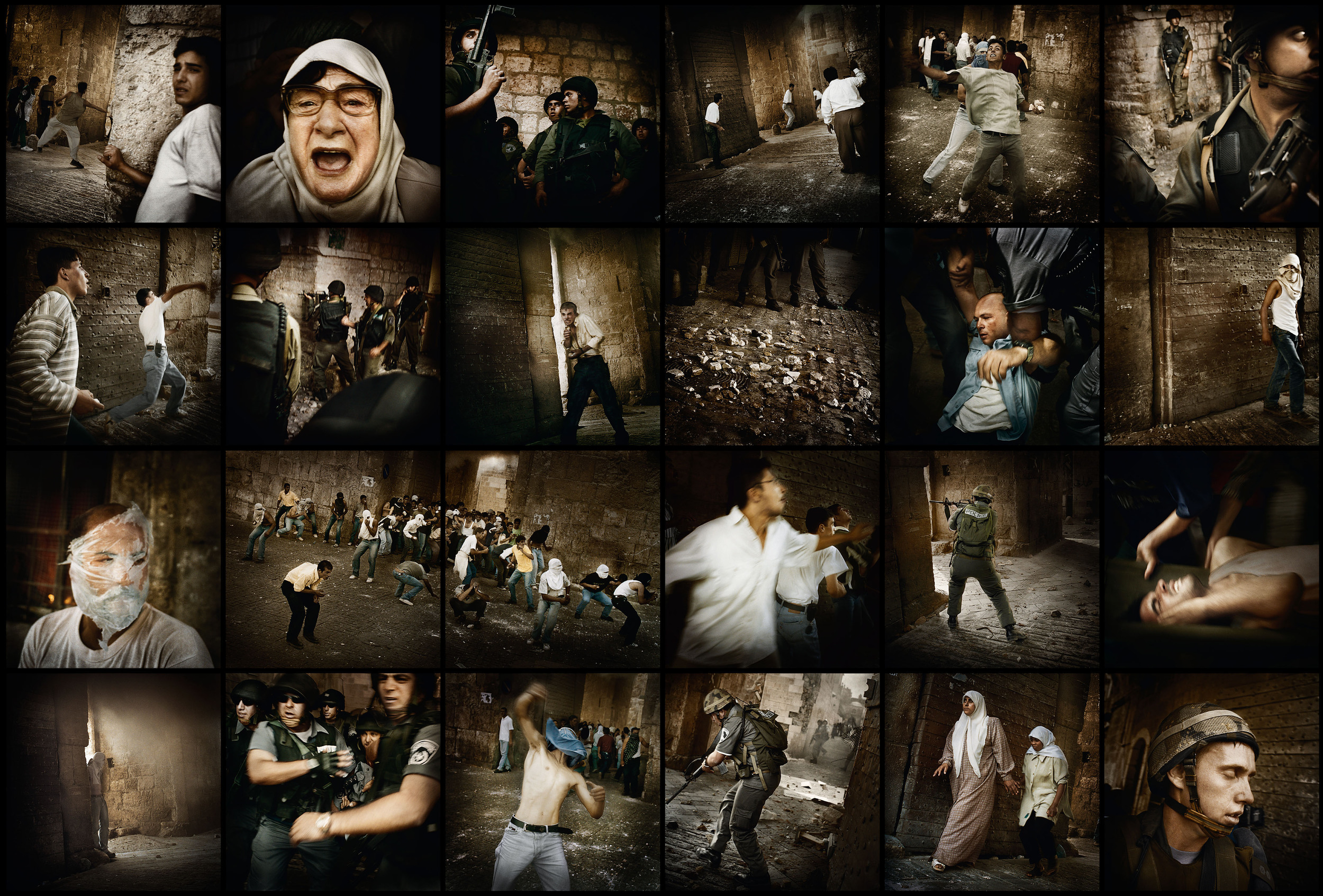

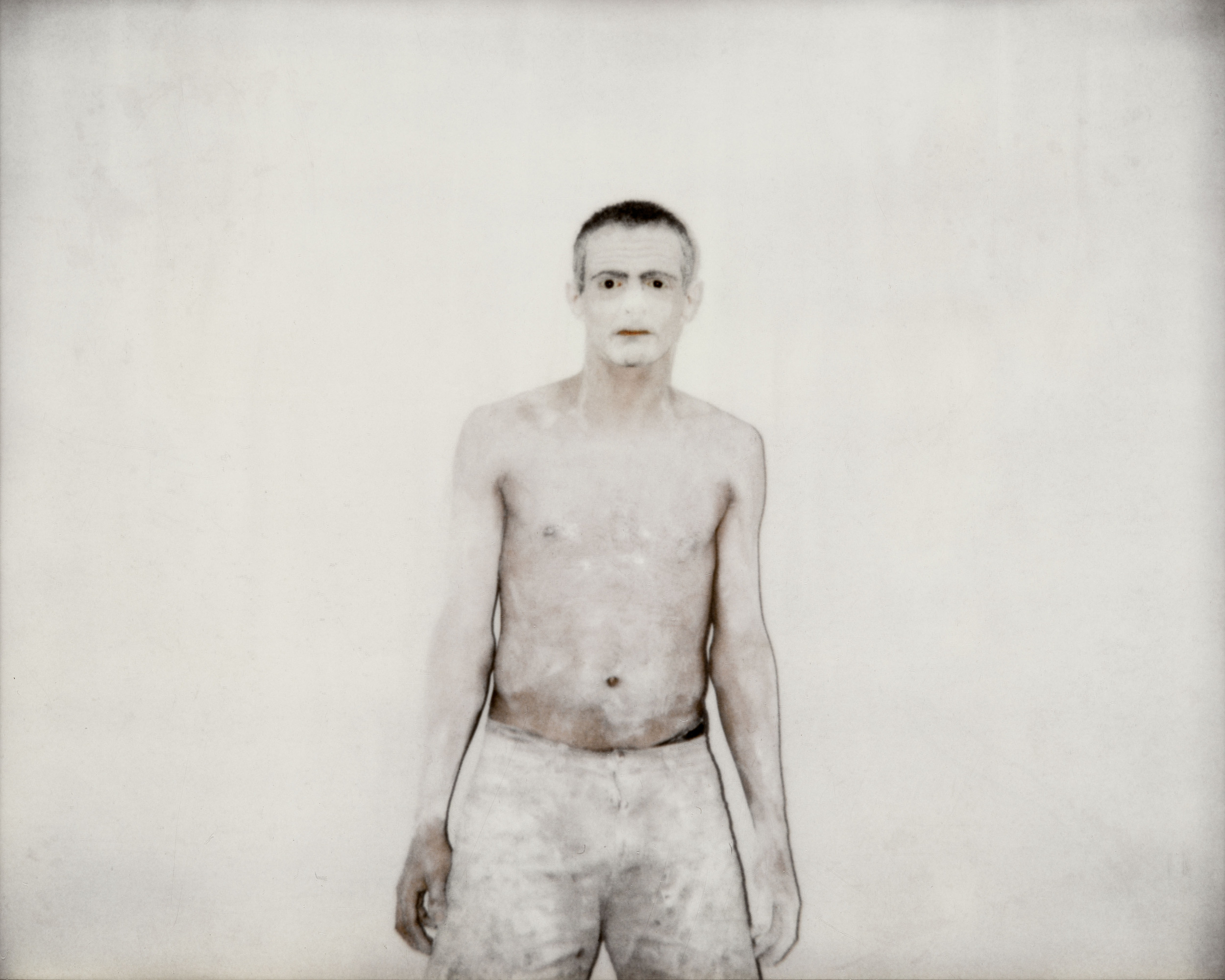

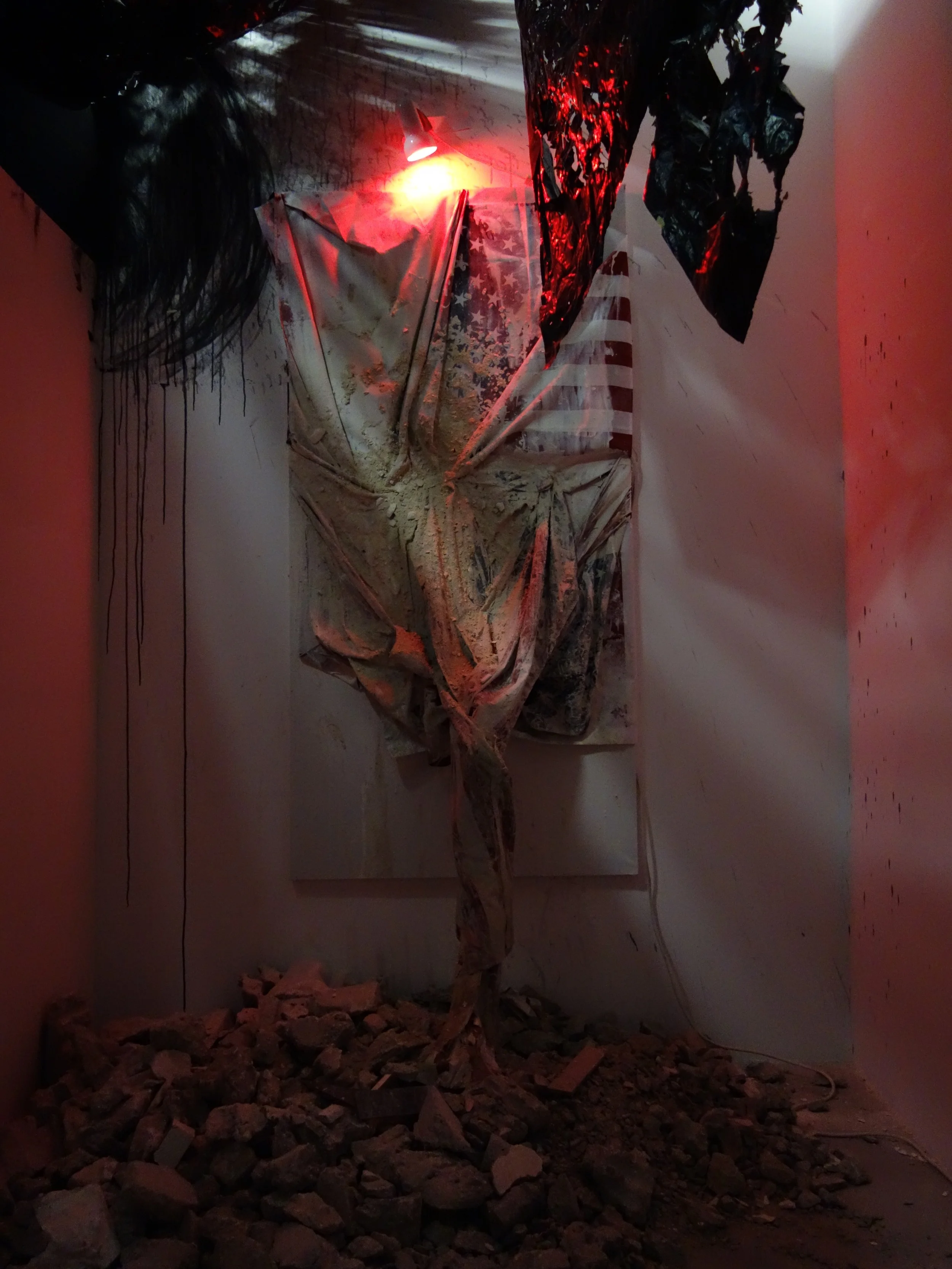

Equal parts addict, biographer, humanist and savant, Antoine d’Agata is a resilient artist who resists falling hostage to any one medium through an evolving practice that dilutes the distinction between living and making. His emotive body of work spans over a quarter-century and actively uproots firm classification within the art historical cannon. Rather, D’Agata’s striking photographs, films and publications eek out an altogether new ecosystem for self expression that is forever nourished by his rare curiosity, unhindered pursuit of adrenaline, and willingness to go where traditional documentarian methodologies dare not tread.

In D’Agata’s artist statement, he illuminates the categorical limits of photography and outlines the strong ethics that shape how he employs it. “Instead of reducing photography to the sole capacity of recording reality, I take responsibility for the position I assume. Rejecting voyeuristic or sociological standpoints, the images ensure art and action are inseparable in the frantic search for the feeling of being alive, of being part of life. In this fragile attempt, the image is defined both through and within the act that engenders it. It’s not my insight into the world that matters but my most intimate rapport with that world."

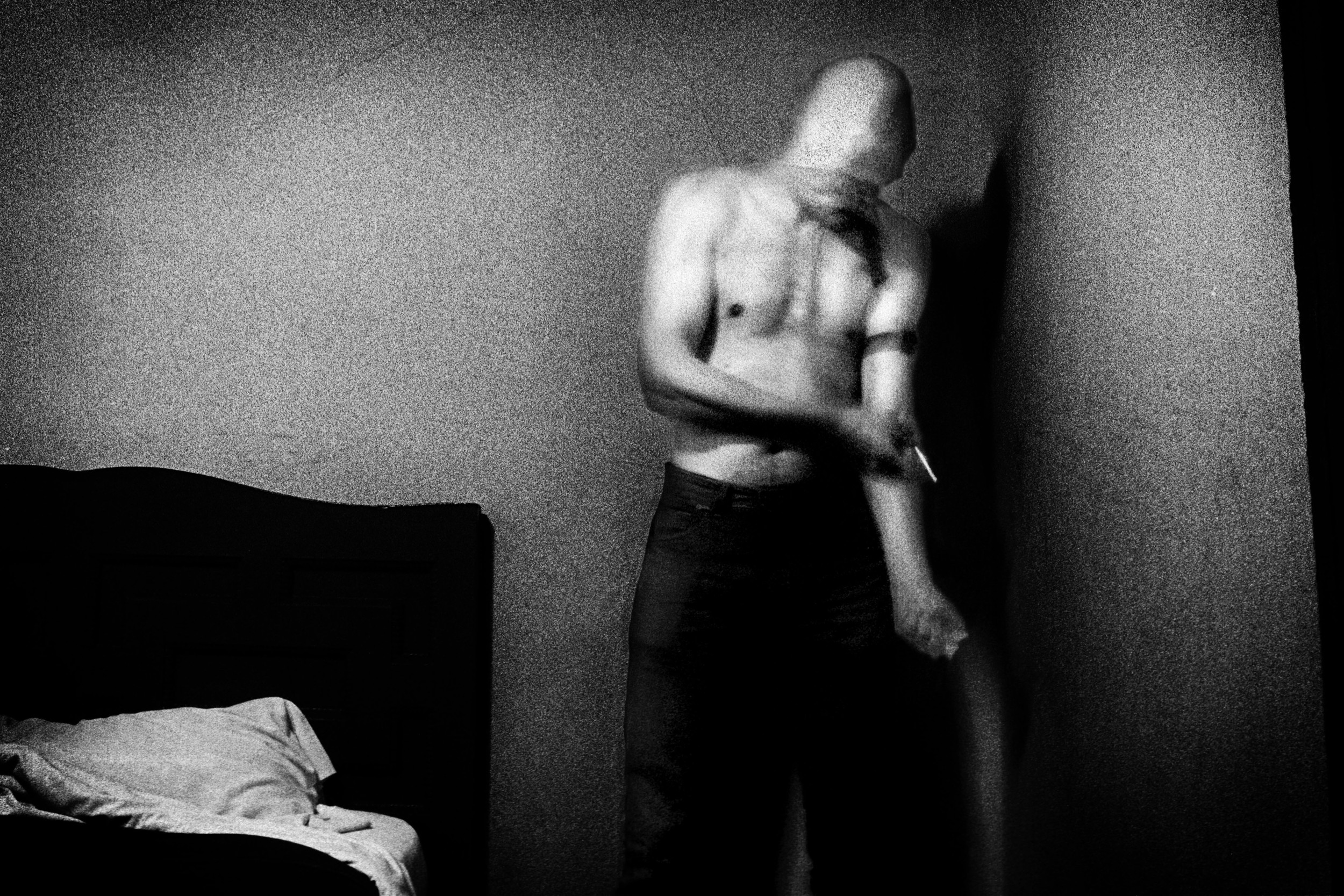

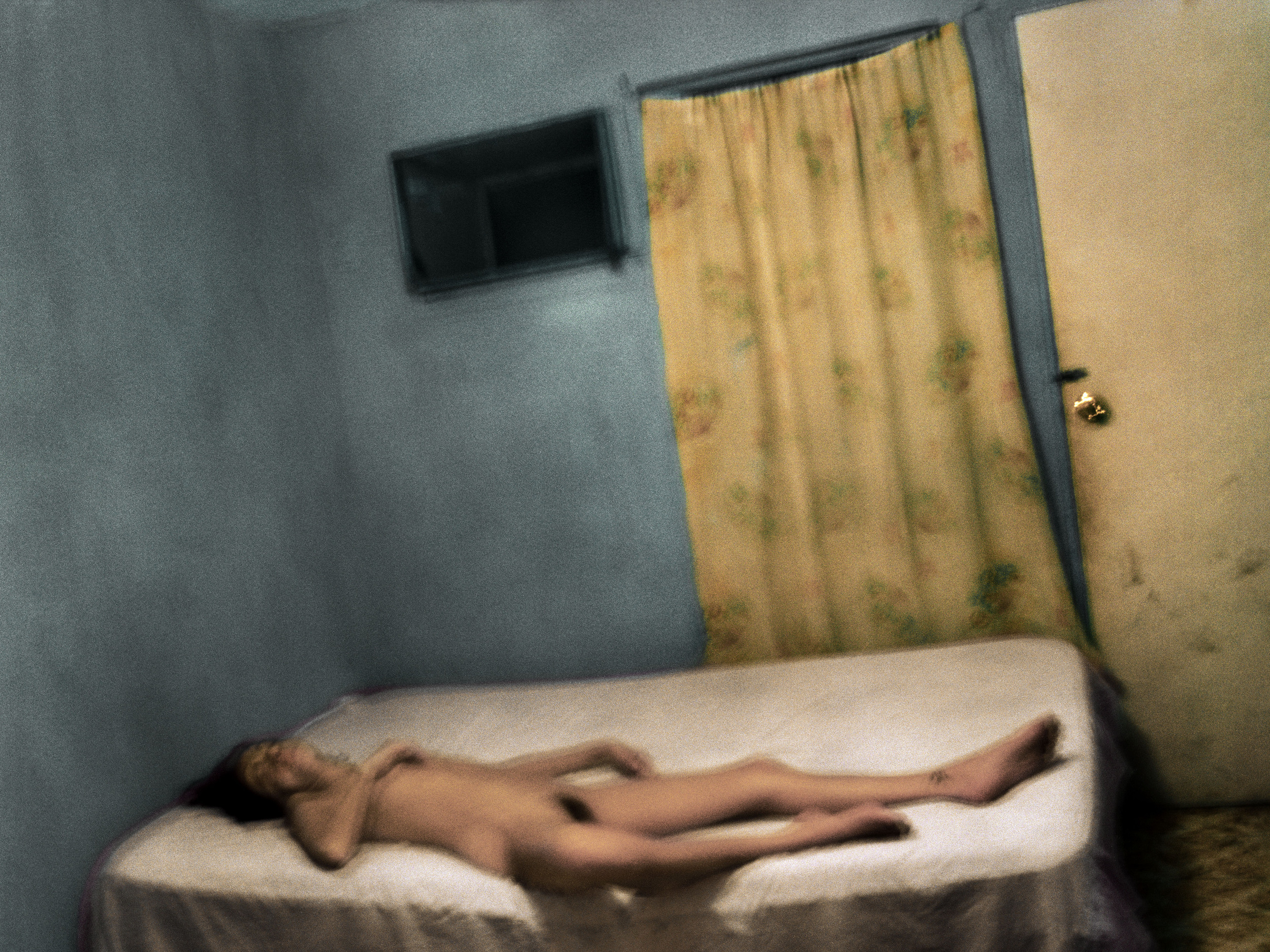

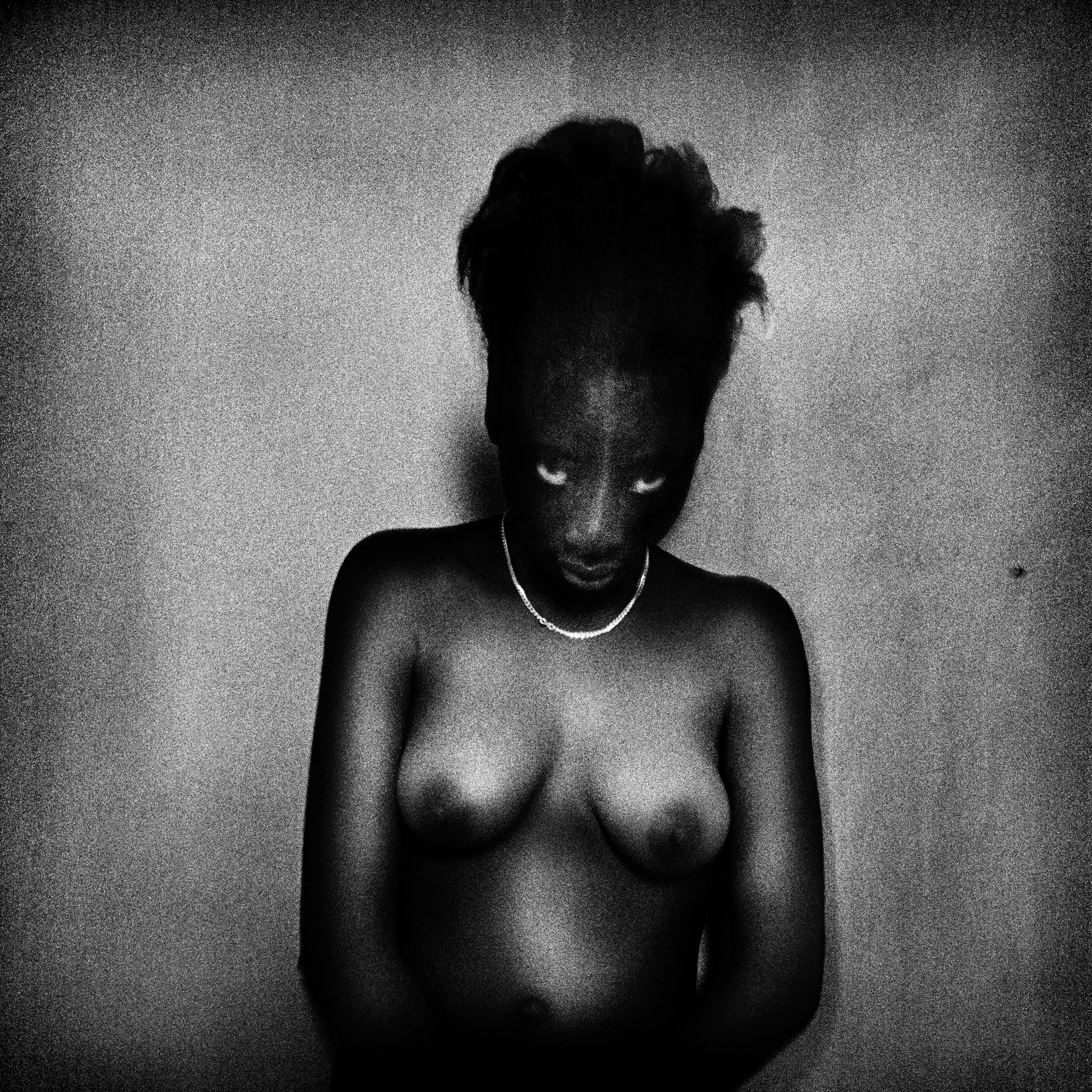

This world that he references and inhabits is most authentically characterized by the people that comprise it—sex workers, drug addicts and, in more general terms, those whose reality is directly and complexly tied to their own bodies. While D’Agata immerses himself within these subcultures, absorbing and incubating contagions without hesitation, his participation is a reasoned choice, bound on all sides by his lifelong commitment to adulterating the physical and cerebral divide. It is important to note that these are not anonymous encounters documented in his works, and are rather moments of solidarity and respect that aim to capture those rare and waning twinklings of humanity. D’Agata is most invested in this aspect of photography that necessitates his presence, and is very vocal about outlining his agency and responsibility in these situations of his own making.

I was fortunate enough to catch up with Antoine upon his return from Cambodia where he was shooting Oscurana, a film on his relationship to methamphetamines and damaged territories that have survived the hardship of war and communism. I spoke with him about truth, death, and love, and asked him to unpack the role sex, drugs and art play in reaching utopia.

N: In your artist statement, you assert, “life overcomes art, and art perverts life.” Can you elaborate on what this means, both in your personal experience and for the field of contemporary art? How do sex, drugs and itinerancy help you to overcome art, and why does it need overcoming?

A: I always refused to play the game of art. I see the artist’s posture as fake, as hypocritical and cynical. My sanity has always been based on my capacity to go back to my very basic needs, habits, and addictions. Vice is redemption to me. It is some type of insurance to never give up, to never give in. I was a punk long before I “became” an artist and I’ll still be one long after nobody bothers looking at my images anymore. Art to me has never just been a way to give shape to a vision, a perspective on the world. It’s always been a method to push things further, to structure my struggle with things and beings, to embrace fear and time, to feel alive, to absorb life, to let life absorb me, enter me, to fade into life.

Right now, I am waiting for the meth to slowly evaporate from my blood, from my flesh, from my brain, and I struggle to keep some kind of sanity, of distance, of lucidity. But even this state of confusion, this banal nightmare is more precious than health, more rewarding than safety. Pain is a privilege; I use the excessive scenario I describe as an incentive to survive, to never give in to the temptation of comfort. To never feel numb again. The art world doesn’t mean anything to me, but I try to adopt the intransigence and dark beauty of that impossible position towards my own existence, and in all circumstances, that position, fatal but gorgeous, where all acts answer the necessity of merging fear with desire. Of using pain, ecstasy and violence as sensorial and existential means, of recognizing addiction and promiscuity as the most adequate social postures, of seeing, and evil as an antidote to the slow death of the consumer.

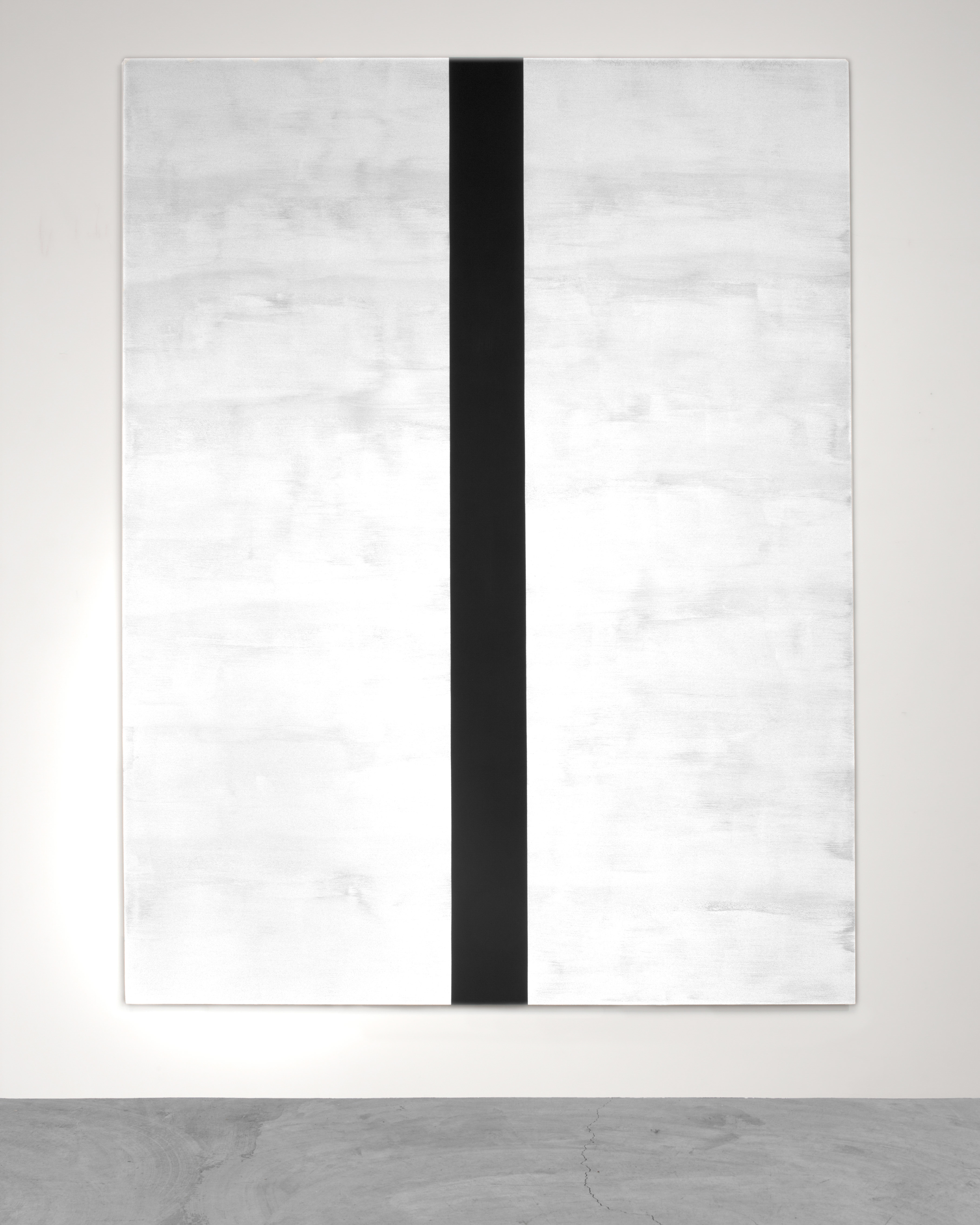

N: In what context do you most desire your work to be consumed? I know you have published numerous books and I wonder if the intimacy of physically encountering your work is an intended outcome, as opposed to the sterility and forced distance of the white cube?

A: These days, it all feels like a compromise. I wish I could just get on with my life and not exhibit or publish, but I am condemned to find an impossible balance between life and giving an account of my acts. This impossible point is what I pursue and I’ll use anything that can help me to fit the purity of experience and logics of ideology into each one of my actions. Books, exhibitions, drugs, encounters are all just tools to me. Without any hierarchy, without any craftsmanship, without any illusion.

N: In more recent years, you have opened up your practice to include film. What are the limitations of photography as a visual language? What flexibility has film provided you, and how has it changed your relationship to the subjects or situations in front of the camera?

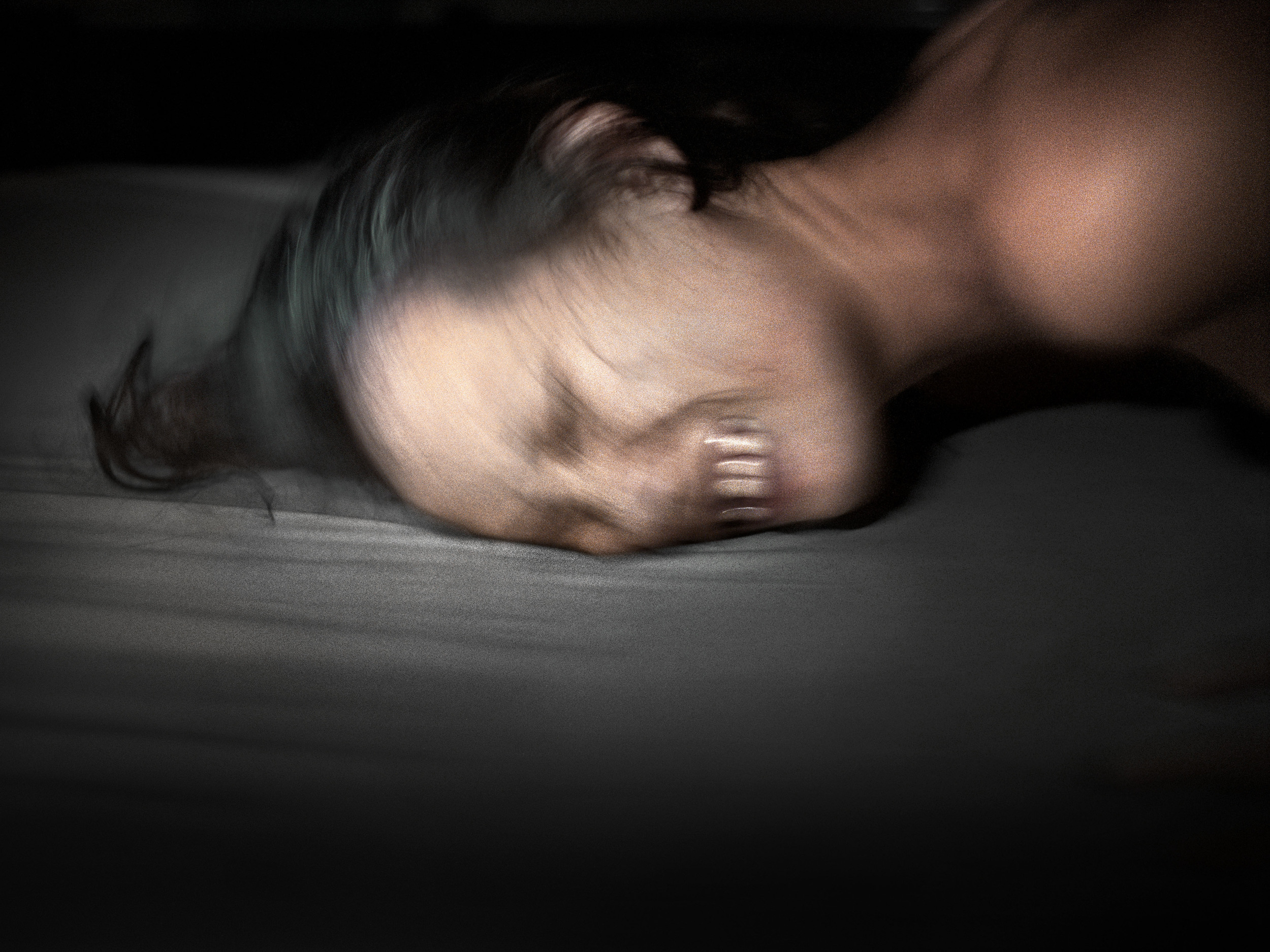

A: The last few years, I have not known what to do with photography. It became too simple, too easy, and too obvious. Film brings me back to dealing with reality, in its more imperfect and more frustrating aspects. While filming, I have to take into account the intensity and truth of situations. Filming generates a language dependent upon truth, while photography fast becomes a game, a lie made out of shades and shapes. I create my own destiny through stimulation of the senses, through excess, and try to develop a language that is appropriate to describe the process. Film became a more meaningful way to speak about what I go through, a more powerful means to challenge the truth and intensity of relationships doomed to nothingness, that I relentlessly nourish to transform into some degenerated form of love. Photography is more of a solitary practice.

Filming is more of a common language developed trough the generous and prolific affirmation of existence imposed by the girls themselves. They share more, embracing fully the excitement, nervousness and danger of facing a more straightforward and honest live camera. Most of all, they accept the challenge of speaking up to the camera, of revealing unveiled aspects of their mental and emotional states, of their relation to me, to men, to the violence of the world. Filming proves itself a fuller and purer experience of sharing bits and pieces of life, but the technical and financial pressure is great; the economy of working with film, the necessity to fund projects, to work with a team of people more qualified than I’ll ever be with cinematographic techniques makes it an almost impossible task.

N: I have often heard your work described of as dark or violent, which to me are terms that lack granularity. What do darkness and violence mean to you and what other words might you use to describe your work?

A: To reinvent a very ordinary destiny, I was bound to lose control, to throw myself into the unknown, into the obscure margins of city life. Considering the logic of my research, this loss into darkness was probably essential and I ended up learning from, loving, desiring, and respecting the beings that inhabit those dark territories. The darkness you speak about, I see as a luminous, generous, dignified land. The women I photograph are saints, heroes, myths, whatever you want to call them. But they are the only beings I can think of who live their life to the extent of their humanity. They are the last human beings in a world of cowards and cynics. This is what darkness is made from...sparkles of life in a world of illusions.

Its possible I’ve never been as close as I am now to what I consider a decent way of living, by my own rules and standards, and among people I consider my own. But plunging into the raw flesh of humanity means intelligence will progressively vanish, and the intuitive violence of the animalistic necessity to survive, to sense, to exist will slowly take over. My images are generated by an overwhelming and omnipresent violence, but this violence is never aimed at the women I photograph. It is a violence that, even though it often harms its own authors, exists only as an antidote and a response to the economical and institutional violence against the invisible community of those who have nothing. The work is deeply political…photography is only a matter of gestures, not the art of the gaze, but the art of position, of action, of life. This untenable position I am seeking to stand for is my statement, my credo, my standard, my logic and my method.

N: In your artist statement you assert, “Bestiality is the ultimate rampart against the anesthesia of senses and the mindset of a society that defines objects and people as commodity.” How do your encounters with the women you photograph subvert the acts of commodification, fetishization and objectification that so often riddle the traditions of portraiture or reportage?

A: I have never shown any pretense to any kind of purity or perfection. But I don’t see the beings I photograph as subjects, models, victims or citizens. I desire them, I love them, I let them hurt me, and I let them seek revenge if they are too far lost in their own pain to recognize me as a possible ally. I know the tragedy of their existence, the depth of the horror they experience on any given day. I tell them how much I expect from them and how much I am willing to give in return, and none of them should have any reason to follow me, or let me follow them, but they do, almost always, because in that horrifying world ruled by strength and profit, humanity is the last secret key to solidarity, compassion, and comradeship—all ridiculous or forbidden words.

To say it in an ugly way, I photograph prostitutes who are far gone, who because of AIDS, addiction or alienation are out of reach from the desires of common men, from commerce of the flesh, from social mainstream communication…we communicate on the single ground of common addictions. Junky solidarity, that’s what saves me from becoming a photographing asshole…

N: You’ve also said, “Adrenaline and pheromones are remedies to social lies in the void left behind by the standardization of consciousness.” Am I right in asserting that adrenaline and pheromones have become lifelong obsessions for you? What lesser-known obsessions do you have and how does photography help you to explore those?

A: My one and only obsession is to make the best out of my existence. To keep struggling to be alive, to not surrender to fear, to keep searching for every unknown way to experience the nonsense of life through my own senses, to keep being excited and scared, to keep taking risks, to keep provoking encounters which force me to choose a political and intimate position, to keep inventing my own life as I would write fiction, and to live up—through gestures—to my words and beliefs.

My own private obsessions, desires, background and traumas don’t mean much to me…At least, I try to ignore them and live up to the pain of the ones who accept me into their world. That’s my way of being social…No narcissism, no self-indulgence, no interest in my own little burdens. In that way, I live a very militant, or sacerdotal life…I see my practice as a very demanding choice, which basically comes down to being a mere sacrifice. But sacrificing oneself for what you believe in is more than foolish or terrorist logic; it is what I see as living in a dignified way, as trying to be a decent human being.

N: Let’s move on to your private life, if that is something you own or believe in. In many ways, you embody the term global citizen and have made numerous countries your home, including England, Nicaragua, Cambodia, Japan and Mexico. How does traveling—possibly even escapism—inspire or affect your practice? Which places have you lived in or traveled to recently, and what about them was most attractive to you?

A: I haven’t had a base for nine years. I live in hotels. Faced with the difficulty of financially surviving, the physical exhaustion, I remain a nomad. Of course I am conscious that part of this capacity to move through the world’s circles and borders comes from the incapacity to confront more stable paths, spaces or relationships. I became a handicapped person in many ways but, even though it differentiates me from the people I photograph, this can be very painful. I chose to preserve and nourish my freedom…I paid the high price over the years for this liberty to draw my own destiny, and I won’t give it up for anything I can think of. I just sometimes choose to take more time, to take more care, to accept the responsibilities generated by friendship, or simply to loose myself deeper in some more somber or more exalting addiction.

The place dearest to my heart these days remains Phnom Penh. There I no longer feel like a stranger, and I immerse myself deeper into the violence of the world, drawing the force to continue from the shared experience of a desperate desire. There I find a fragile solace for the slow decrease of my strength to act. The acute awareness of still being alive. I improvise my life, which gradually resembles an exercise in overtaking art, or the fulfillment of an ancient utopia; the abolition of speech in favor of what is lived.

N: How did your time living in New York and studying photography at ICP in the mid-nineties evolve or change your practice? And whom did you meet there—aside from mentors Nan Goldin and Larry Clark—that changed the way you saw the world?

A: To me, New York was a break, a breath…the city gave me the strength and energy to keep going. Living there gave me the opportunity to see the beast from within, to understand, or at least feel, its intimate logics, its emotional and cultural background. To live within a society that I condemn as a political entity and negative economic force has proved useful over the years, in expanding my understanding of cruelty, banality, naivety and cynicism. I understood that good sentiments hardly, if ever, translate into meaningful actions. I understood that comfort is the worst possible way of life. I understood that fearless desire generates armies of morons, and that fear without desire gives birth to generations of slaves. I understood that you couldn’t listen to your heart, mind or body and have to venture deep inside the dark territories of instinct.

I chose the dark side of things, resisted the refined temptations of economical and moral well-being and doing good. I renewed my old allegiance to the world of misfits, outcasts and degenerates…I kept exploring social territories humanly damaged by the economical process that allows American society to feed and reproduce itself over the condemnation of entire rejected or negated communities.

N: And then you took a break from photography. What did you get up to next?

A: I studied photography when I was thirty and stopped photographing when I was thirty-two. Then, I was working long shifts to raise two baby girls born in 1994 and 1995. I started to photograph again when I was thirty-six or thirty-seven. Two daughters were born since, but I never stopped shooting after that.

N: What role have your four daughters played in your life? You mention in past interviews needing a tether to reality at times to achieve balance, and that proximity to war has served as one form of therapy for you in this way. Do your daughters also help to ground you?

A: They do. They are part of this fragile balance, even though they should not be. I should be the one providing them with arms and ammunitions. But they know I live by my own rules. They know it’s a loosing deal for all of us, as a family. I believe they understand, in some strange way, and respect my intimate agenda. I am forever indebted to them.

N: Do you believe in love? I guess I’m not after a definition of romantic love here, but rather a description of the possible forms with which it manifests in your life.

A: I could say that the only form of love I consider valid is whatever subtle mix of lust and understanding two or more people share in any given moment, that doesn't need or require any type of payment, consolation, compensation, or reward of any type, be it financial, social, intellectual or emotional. But love is the opposite of all proposed definitions; it is something that won’t make sense, but sticks to you and to others, something you can’t get rid of, against all odds and logic. Love is most beautiful when it doesn’t make sense…So let’s not try to make sense out of it…

N: And what about death? Do you think the act of aging and nearing a more finite definition of death will slow you down in any way? Or do you perceive of death the same way you do other obstacles to self and consciousness, as something to be confronted head on?

A: Photographing, as any other human activity, only makes sense when confronted with the threat of death, or at least its presence or ineluctability. Life then definitely takes on more weight, more responsibility. Provoking other experiences, other intensities, confronting my doubts and my contradictions, documenting the slow decay of the body with the little time left is what I am busy with these days, photographing less and less, struggling more and more. A loose journey, a slow kind of agony exhibited for all to see, a form of true liberty.

I observe the fading breath, the nervous system's shut down, the weakening of the organs. While fewer pictures are taken, while the takes become sparser, more painful, I’m aware I’ve never felt so peaceful. I am slowly becoming at peace with others, and with myself while struggling to keep the risks high, the fear intense, and the desire genuine, without feeling ashamed anymore of being compassionate. While the flesh little by little dissolves in the shadow of death, the soul becomes brave, because it was made not to fear, not to ignore, not to forget, not to shy away from that absurd void surrounding us.

N: And what or whom do you think awaits you in the afterlife? Does your constant pursuit of utopia here on earth in some way acknowledge that there are mental and physical limits to enlightenment?

A: I never wished or believed to trespass any limits by my own. It is all about the limits. It is not about getting anywhere. It is about not giving up trying. There is nowhere to get to, no secret to unveil, no magic territory to walk through but the territory of our own fear. It’s all about walking straight, about wanting to feel the pain until the very last minute, refusing wrong ways of escape, inglorious aesthesis, lame defeat of the soul through ideology and religion, shameful comfort of the senses, or the hypnotic efficiency of the spectacle. It’s all about reinventing one’s own destiny every day, beyond reason…

---

Born in Marseilles, Antoine d'Agata left France in 1983 and remained overseas for the next ten years. Finding himself in New York in 1990, he pursued an interest in photography by taking courses at the International Center of Photography, where his teachers included Larry Clark and Nan Goldin. During his time in New York, in 1991-92, D'Agata worked as an intern in the editorial department of Magnum, but despite his experiences and training in the US, after his return to France in 1993 he took a four-year break from photography. His first books of photographs, De Mala Muerte and Mala Noche, were published in 1998, and the following year Galerie Vu began distributing his work. In 2001 he published Hometown, and won the Niépce Prize for young photographers. He continued to publish regularly: Vortex and Insomnia appeared in 2003, accompanying his exhibition 1001 Nuits, which opened in Paris in September; Stigma was published in 2004, and Manifeste in 2005. In 2004 D'Agata joined Magnum Photos and in the same year, shot his first short film, Le Ventre du Monde (The World's Belly); this experiment led to his long feature film Aka Ana, shot in 2006 in Tokyo. Since 2005 Antoine d'Agata has had no settled place of residence but has worked around the world.

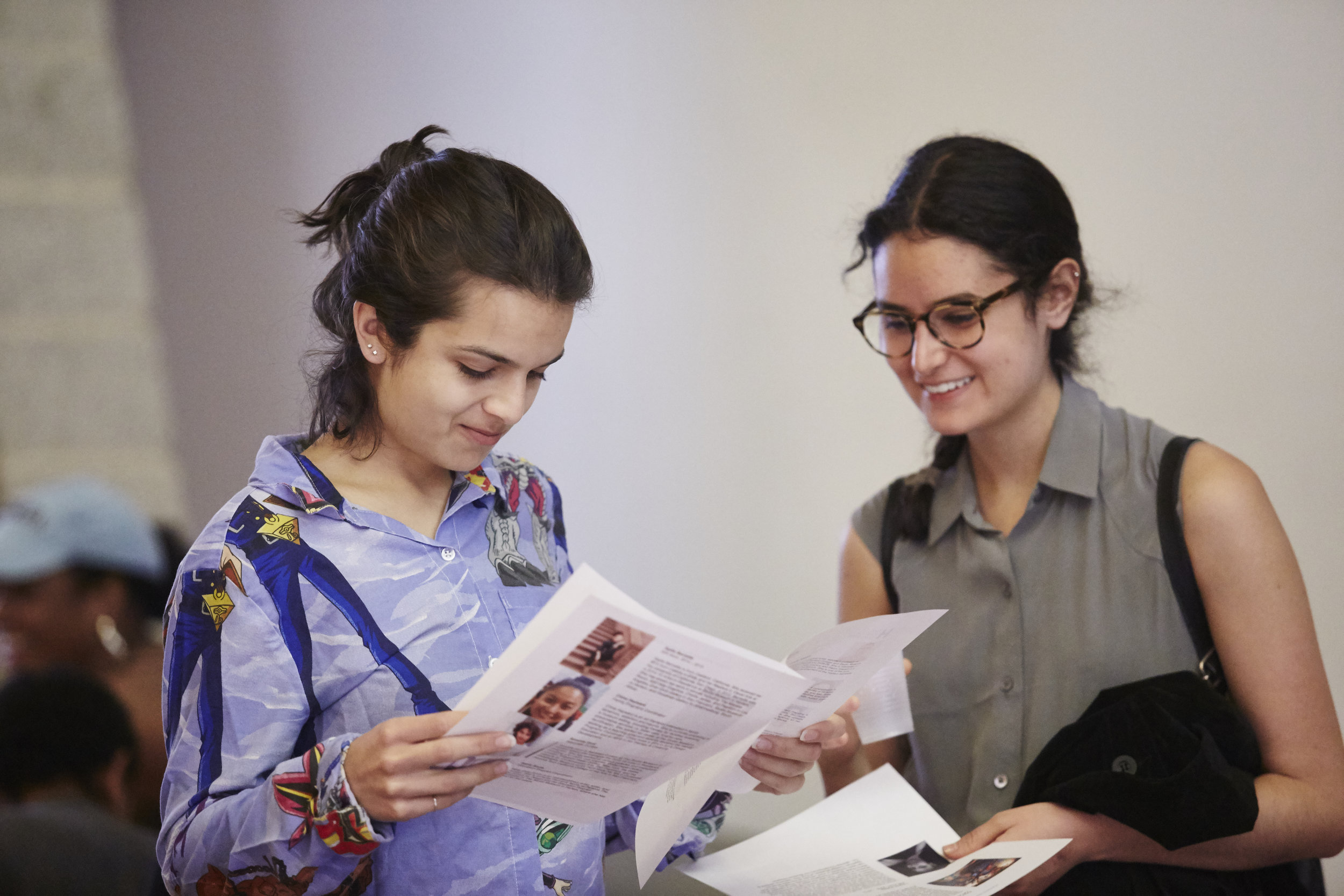

Published in NOTOFU Magazine, Winter 2015 Issue