MoMA | OCTOBER 7, 2018 – JANUARY 13, 2019

Celebrated for his mastery in mark making that captured Black dignity, suffering, and triumph, Charles White has only recently gained acclaim as a devout educator and pioneer in social practice. While his artworks took many forms over the years—spanning the canons of painting, drawing, and public art—they share an emotive formalism, powerful enough to carry the torch of the Black Chicago Renaissance, and speak across the many binaries of the civil rights movement. White only lived to the age of sixty-one, however, his prolific career spanned four decades, and now—four decades later—the full extent of his legacy and influence on generations of artists is finally being lauded by mainstream arts institutions beyond his native Chicago. His stunning retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art is divided chronologically into six sections, each of which explores a defining era in the artist’s all too short, yet profoundly impactful life.

Charles White, Five Great American Negroes, 1939. Oil on canvas, 60 × 155 inches. From the Collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. © The Charles White Archives. Photo: Gregory R. Staley.

Throughout his career, White dutifully rejected the dominant images of African Americans in circulation, exercising his artistry as a tool for rectifying misperceptions and reclaiming the narrative of black culture within American history. He once stated, “Because the white man does not know the history of the Negro, he misunderstands him,” and many works in the first section of the exhibition embody this tension between perception and reality. For his 1939 WPA (Works Progress Administration) mural Five Great American Negroes—his first public mural and the first piece one encounters as they approach the galleries—White depicts Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver, and Marian Anderson in vibrant colored oils on canvas. He plays with perspective in this large-scale work to foreground these pioneers in African American history, while simultaneously distorting the background—or terra firma—on which these greats so precariously stand.

White arrived at these figures by working with The Chicago Defender to mobilize the South Side in revisiting the contributions of African Americans to American history, and voting for whom they wanted to see represented on their walls. This gesture would become a recurring theme and position in White’s practice—that African Americans are the authority on the Black experience, and that art can carry this agency, even when the world it depicts can not. A graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and member of the Sponsoring Committee of the South Side Community Art Center, White’s commitment to arts education is evidenced not just in the social and cultural institutions he helped build there, but also in the collaborative processes behind the creation of his murals.

Charles White, Kitchenette Debutantes, 1939. Watercolor on paper. 27 × 22 7/16 inches. Private collection. © The Charles White Archives. Photo: Michael David Rose.

White came to prominence in an art historical moment of abstraction, thus making his choice to see and depict Black humanity through figuration a supremely political one. White’s early works share an illustrative, expressive style that boast both a formal and cultural accuracy in regarding the black figure—a striking aesthetic quality not, however, to be overshadowed by their blunt political commentary. In his 1939 watercolor Kitchenette Debutantes, White called out the horrific living conditions so many African Americans faced living in overcrowded apartments on the South Side. Here, he lends his skillful mastery of light and color to represent two local women, whose shapely forms occupy the near entirety of the angular window frame. The tension between curve and line—dark and light—amplifies the viewer’s sense of both their cramped quarters, and the vast distance between the American dream and the lived reality of African Americans at the time. Aside from its formal brilliance, the scene bears expert witness to the resilience of the Black spirit and imagination—despite the ways this world would render these women invisible, their gestures and facial expressions affirm their self-determination to find beauty in their surroundings and mirrored reflections.

An artist and advocate in touch with the struggles of his community, White was as committed to representing the injustices they faced as he was to depicting their strength to overcome. In the early 1940s, White continued to speak out against America’s legacy of systemic oppression, deploying the hyper-visible visual language of murals to educate and empower communities of color. During this short period of time, he produced three large-scale murals that drew on his experiences traveling to Mexico with Elizabeth Catlett—a formidable artist and his first wife—and the technical skills he gained working with Mexican printmaking collective Taller de Gráfica Popular. As the exhibition moves from White’s Chicago years to the formative time he spent in New York working under the influence of Catlett’s own distinct monumental representations of the bodily form, viewer’s are confronted with a notable shift in White’s work, one that take us from color to black and white, painting to lithography, and the site-specificity of murals to easily replicable works on paper.

Charles White, Harvest Talk, 1953. Charcoal, Wolff’s carbon drawing pencil, and graphite, with stumping and erasing on ivory wood pulp laminate board. 26 × 39 1/16 inches. The Art Institute of Chicago. Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert S. Hartman. © 1953 The Charles White Archives.

In The Return of the Soldier (1946), he explores the historical and disposable role African Americans have played within America’s so-called democracy, first as slaves and unskilled laborers, and then as soldiers and veterans during World War II. Here, we see White making painstaking use of repetitive fine lines, the density of which produces a near-pitchblack scene from which the figures of a policeman and Klan member emerge, as they loom over three Black soldiers huddled together on the ground. White graphically deploys pen and ink to rewrite the story of the African American soldier in its sad truth—how many returned to social injustices in their own country, as violent and militant as war, and far worse than anything they’d seen abroad.

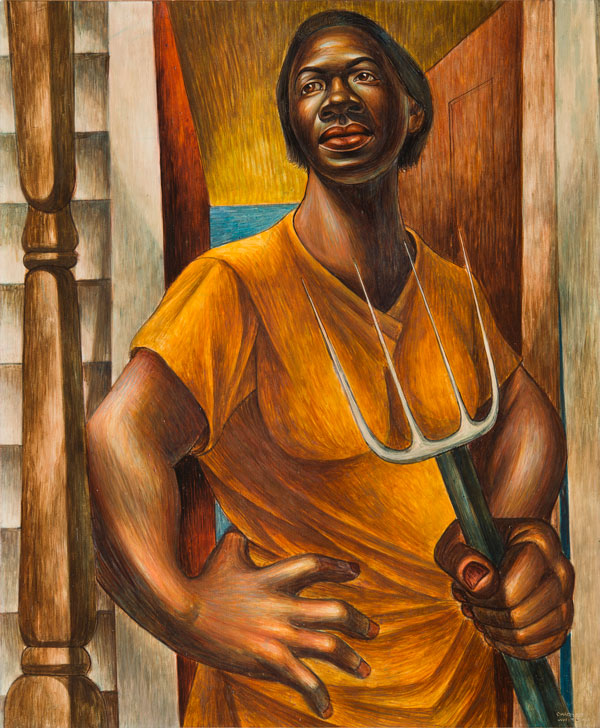

Charles White, Our Land, 1951. Egg tempera on panel, 24 × 20 inches. Private Collection. © The Charles White Archives. Photo: Gavin Ashworth. Courtesy Jonathan Boos.

His pro-labor, socialist political stance was ever visible, and in the ’50s he increasingly elevated the image of the laborer by depicting large, spectacularly rendered hands, and bodies of monumental proportions in works such as Our Land (1951) and Harvest Talk (1953). As pre- and post-war America saw a rise in illustrative propaganda, White rode the wave, strategically reproducing his works on paper in ads for black-owned businesses, in leftists journals such as Freedomways, The Daily Worker and Masses & Mainstream, and on album and magazine covers. Iconic works such as J’Accuse #10 (Negro Woman) (1966)—which flanked the cover of a special issue of Ebony Magazine that same year—were widely and regularly circulated, which meant their political messages would reach the broadest possible audience. Despite their commercial or editorial contexts, these works maintained the status of high art, and transcended potential slippage into the flattened realm of illustration.

The exhibition then transitions into his later years, a time when his appreciation for the contemporary contributions of Black people to American history led him to entertainers who—like himself—carried the story and spirit of Blackness in their artistry. At the same time he was building community in Los Angeles amongst Black Hollywood, White began to teach at Otis Art Institute, where he influenced the budding practices of world renowned artists Kerry James Marshall and David Hammons. Through both his love of music and passion for teaching, White continued to explore the social aspects of art that intrigued him, celebrating the power of music and education to put forth a new vision for universal humanity. In his May feature in the Paris Review, pupil Kerry James Marshall finds the perfect words to capture White’s influence, legacy, and skill, stating: “He is a true master of pictorial art, and nobody else has drawn the black body with more elegance and authority. No other artist has inspired my own devotion to a career in image making more than he did. I saw in his example the way to greatness. Yes. And because he looked like my uncles and my neighbors, his achievements seemed within my reach.”

Marshall’s words are pregnant with the possibility that White inspired in others, but also speak to the internal drive with which White continued to push his own practice forward. One gleans in these final stages of the exhibition that teaching had a remarkable influence on White, as students pushed him to reexamine his own form and content. The last decade of White’s career was a period of bold experimentation during which he developed a collaged approach that layered oil painting, drawing, and text. Black Pope (1973), an iconic image for which he might be most well known, depicts a robed Black man in sunglasses wearing a sandwich board who, through a unique combination of gestures and props, takes on a regality and dignity despite the inference that his congregation might be on, and of, the street. A skeleton, crucifix, and the word “Chicago” looms overhead, leaving visitors exiting the exhibition to reflect on White’s message, and singular ability to deploy art as both a language of resistance and tool for social cohesion.

Charles White. Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man), 1973. Oil wash on board. 60 × 43 7/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Richard S. Zeisler Bequest (by exchange), The Friends of Education of The Museum of Modern Art, Committee on Drawings Fund, Dian Woodner, and Agnes Gund. © 1973 The Charles White Archives. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar, The Museum of Modern Art Imaging Services.