NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART | NOVEMBER 4, 2018 - FEBRUARY 18, 2019

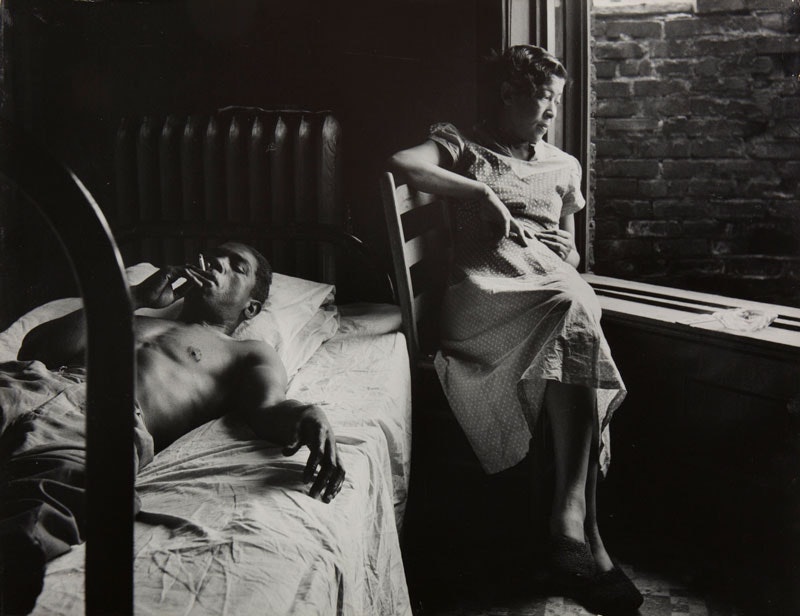

Gordon Parks, Tenement Dwellers, Chicago, 1950. Gelatin silver print, 10 3/4 x 14 inches. © and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation.

“We are with the new tide. We stand at the crossroads. We watch each new procession. The hot wires carry urgent appeals. Print compels us. Voices are speaking. Men are moving. And we shall be with them!” - Richard Wright, 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, 1941

If Wright’s “new tide” embodies the wave of social change that engulfed a segregated 1940 America, Gordon Parks was an essential gravity that washed the revolution ashore. An icon of the Chicago Black Renaissance and postwar Harlem eras, Parks was a self-taught, genre-defying artist whose talent spanned photography, music, writing and film. While he is lesser know as the pioneering director behind the first blaxploitation films of the early 1970s, Parks’s centering of resilient, black protagonists as the heroes of everyday life dates back to his early years as a celebrated documentary photographer. The New Tide, Early Work 1940 – 1950 bears expert witness to the impact of Parks’s formative assignments, capturing untold stories across the industrial Midwest and Northeast, on launching his prolific career. The exhibition is comprised of 150 black and white photographs, presented alongside rare, archival ephemera, including confidential files, magazine clippings, interpersonal letters, and family portraits. An illuminating early-career survey, it too foregrounds the haunting realities of post Depression-era American life, and honors the men, women, and children who struggled behind the scenes to endure it. The exhibition is laid out in five sections that chronicle the decade in which Parks found his voice as an artist, and honed his craft as a tool for social justice: A Choice of Weapons, Government Work, The Home Front, Standard Oil, and Mass Media.

Gordon Parks, Langston Hughes, Chicago, December 1941. Gelatin silver print, 13 1/8 x 10 5/8 inches. © and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation.

In A Choice of Weapons, we begin at page one of Parks’s budding portfolio—a series of striking black and white portraits taken a little over a decade after the decision to buy his first camera from a pawn shop at twenty-five. In retrospect, Parks famously said, “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.” A bold proclamation of solidarity, his first professional portraits somewhat ironically depicted household names such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Alain Locke, Charles White, and Langston Hughes captured in simple, playful compositions. Over the span of four photographs, we follow Hughes as he moves through levels of consciousness, guided by Parks: a pensive moment leaned against the back of a chair; a rebellious insertion of his form behind a painting frame as a work of art; a joyful expression as he gazes into the distance alongside a figurative sculpture that he holds in collegial embrace; and a return to the frame where, this time, his somber expression and flat palm forebode an inability to break the plane between foreground and background, art and life.

In considering Parks’s humble roots—and his rapid raise from being the youngest of fifteen children on his family’s farm in a small segregated town in Kansas, to intimately capturing the nation’s most prized cultural luminaries through his self-run portrait business—it would be easy to position Parks as a proxy for upward mobility and pursuit of the American dream. However, as the exhibition unfolds, it becomes clear that—despite his artistic gifts and the rare opportunities they afforded him as a black man in a segregated country—Parks was still very much of and for the everyman. Government Work presents a series of photographs that reflect his time working as a documentary photographer for the Farm Security Administration, a funded position he secured through the coveted Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship.

Under the conservative yet tutorial direction of FSA head Roy Stryker, Parks set out on national projects that sought to “humanize” the working poor as part of a documentary photography movement. Central to the political agenda of this government initiative was generating an accurate historical record, whilst also producing digestible images that could be publicized to show that American progress was in the works. However, Parks’ own experiences of racism and oppression in the capital city led him to take his assignments a step further, rendering visible the invisible and deploying his camera to celebrate survival as an artform in and of itself. Notably, his unparallelled vision and uncompromised style refigured the way a divided nation regarded its shattered reflection. In piecing the bigger picture together, Parks collapsed the perceived signifiers of class by representing all of his subjects in a dignified light, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Poor children and families photographed in naturally-lit, domestic scenes of simultaneous turmoil and triumph were captured with the same care, intention, and expertise as those Parks had staged of the Chicago elite basking in the bright lights of his studio.

Gordon Parks, Washington, D.C. Young boy standing in the doorway of his home on Seaton Road in the northwest section. His leg was cut off by a streetcar while he was playing in the street, June 1942. Gelatin silver print, printed later. 20 x 16 inches. © and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation.

One of the most striking images in this section is that of a young boy in his doorway, looking out longingly on the street. The view is from behind as he gazes at two young girls on a neighboring stoop, slouched as if returning home after play. It takes a moment to pull the full image into focus and understand the particularity of his silhouette—the boy stands atilt, with two wooden crutches propping up his form, which balances precariously on one leg after the boy lost the other under a streetcar. While sad in nature, there is nothing particularly tragic about the image Parks presents us with. The boy stands at the juncture of the dark interior of his home, and the bright wash of daylight on the street. Everything about his posture suggests that he is stepping into that light, determined to not let his circumstances define him. Another iconic set of photographs is of a young black family in the Anacostia, D.C. housing project. The first depicts a mother peeling potatoes and she lovingly regards her two children playing on the lawn through the window. The tenderness of this gaze will become a motif in Parks’ work, as many of his subjects are captured trapped in the delicate balance between necessary daydreaming and tending to the tasks of everyday survival.

In The Home Front, viewers are confronted with increasingly layered domestic scenes that recall the artist’s own experience of living in and enduring poverty in a small, single family home packed to the brim. In images like Washington (Southwest Section), D.C. Negro Children in the Front Door of Their Home (1942), we see Parks pull back and expand his focus—a loosening up of the taut portrait frame to make necessary space for figurative details and a more comprehensive representation. Five children spill through the screen door of their home, one stacked on top of the other, giving viewers the impression that an accurate portrayal of the emotional and psychological effects of poverty cannot be captured in a single countenance alone. Here, Parks redefines the traditions of portraiture to demand authentic context, and dares to challenge a status quo that struggled to depict poverty and those suffering through it in their full complexity.

In Standard Oil, we follow Parks’s adventures between 1944 and 1948 on assignment documenting laborers in industrial townships across Maine, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and even Canada. These images are strikingly different from the portraits of the first three sections of the exhibition—the lighting is dramatic, which produces a significantly higher contrast and almost graphic effect. We find Parks experimenting with location and scenery, a skill that will ultimately prove useful in decades to come when he begins making films. The most cinematic image in this section—Pittsburgh, PA. The Cooper’s Plant at the Penola Inc.Grease Plant, Where Large Drums & Containers Are Reconditioned (1944)—plays with lighting angles to draw out that slick patina of industry as a well oiled machine.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1947. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 6 7/8 inches.© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Towards the end of the decade that launched his career, Parks extended his vast range of subjects and subject matter to include international fashion models and movie stars for Ebony, Vogue, and Glamour magazines, whilst also documenting the toils and triumphs of a post-war Harlem in photo essays for Life Magazine. The final section of the exhibition, Mass Media, brings together a compelling collection of seemingly disjointed images—the portrait of a young boy choosing between a black and a white toy doll; a patient, head in hands, in a clinic waiting room; street scenes of Harlem, littered with trash and abuzz with life and death; model Sylvie Hirsch donned in a Dior striking a pose on a Parisian street; a young girl holding a baby in Portugal; a young boy aghast gazing upon Babe Ruth in his coffin; and a Harlem gang leader trapped in a house, waiting for the ever-lively street to die down just enough to escape. In this diversity of subject matter, one gets a final and lasting impression of Parks’s commitment to seeing, elevating, and representing the human condition in its complexity. This politic of equitable visibility was unheard of during his time, and perhaps it is only in retrospect that important exhibitions such as this one hold us accountable to confronting the glaring holes in the record of American history. Here, images carry truth in ways that words alone cannot, and Parks’s legacy is confirmed as a pioneering photographer who dared to situate subjects from all walks of life in positions of power, inviting their countenances to tell the true story.